At the annual natural history-focused Wildscreen event in Bristol this week the usual concerns about the decline in traditional business models and stagnant creativity were present, but few threats gripped delegates like that of AI.

Charlotte Moore in conversation at Wildscreen

The natural history genre can often feel like it exists in its own little bubble.

Tucked away in the beautiful Brunel-built city of Bristol, it feels a world away from the London rat race, and with its super long lead times and high budgets also somewhat immune from the peaks and troughs, trends and fads of the television business.

For the blue-chip stuff especially, it’s very rare a head of factual at the BBC who commissions a Frozen Planet, Blue Planet or Planet Earth series is still in situ when the thing actually comes to air four years and several million quid later. Hell, Britain is capable of working its way through half a dozen prime ministers while the NHU, Silverback and the likes are sitting in the same bit of jungle waiting for the same monkey to do this one thing it’s never done before on camera for this one shot in this one episode of this one series.

They get their commission and budget, they disappear into the field for four years, and the entire TV business changes while they’re gone. In the time it’s taken the BBC to film Kingdom, it’s forthcoming 6×60’ blue-chip series in Zambia, we’ve had the Covid-19 pandemic, an enormous content boom like never before, and now a crash of the traditional model which seems to threaten the very existence of the business itself. The industry is wholly unrecognisable from when that show was greenlit. The BBC’s next blue-chip gaps aren’t until 2028/29.

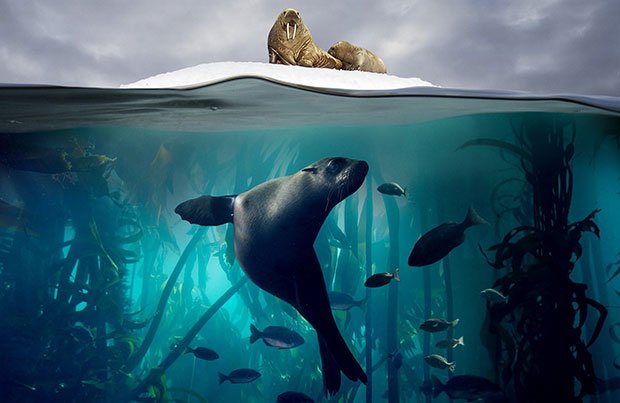

At the annual Wildscreen event here in Bristol this week, the biggest fear to begin with was whether this has made the genre a little predictable, samey… lazy even. Blue Planet II, Frozen Planet II, Planet Earth III, just stick another number on it, get David Attenborough to narrate, Sunday night, BBC One, 21.00. Job done.

BBC natural history’s Blue Planet proved a massive hit

The BBC’s chief content officer Charlotte Moore and head of specialist factual Jack Bootle both faced accusations on stage that, creatively, the blue-chip part of the genre was “stuck in a rut”.

Moore agreed with interviewer Alastair Fothergill, co-founder of All3Media-owned UK prodco Silverback, there was a cold wind blowing through the sector but added: “It’s not just a natural history issue.”

She told industry execs: “There’s also a cold wind blowing through the drama sector; it’s very hard to get coproduction funding for drama these days. It’s the same with comedy and factual across the board.”

Moore said the issue was due to the fact that “audiences are watching content in different ways these days. Even the big streamers are looking at their funding models. These are very difficult times but we have to adapt. To keep audiences watching we have to change our approach to storytelling as well as funding.”

Countering Fothergill’s accusation that the BBC’s natural history is “stuck in a rut, with too many Planets and too dependent on David [Attenborough]”, Moore replied: “With millions of viewers for our shows, it’s a pretty good rut to be in.”

Bootle doubled down on that point on stage on Wednesday.

“I know there has been some chatter here about the health of blue-chip genre and the idea it’s stuck in a rut creatively,” Bootle said. “I do think innovation is really important and we’ve been briefing innovation, innovation, innovation for four years now. But we do have to be slightly careful not to misrepresent scale of the problem.

“There is a feeling of fatigue around blue-chip in Bristol and the sector, but I don’t think that feeling of fatigue is shared by the viewers. In fact, I know it’s not shared by the viewers because I know 10.5m people watched Planet Earth III. That isn’t fatigue that’s enthusiasm. If being stuck in a rut means 10.5m viewers I will happily take it.”

Tough to argue against that. Bringing 10.5m viewers to a linear public service broadcaster on a Sunday night, an audience spread right across the demographics, in 2024? Wish we could all have a creative crisis like that one.

But if we learned anything from movies, in nature, that’s when the attack comes. Not from the front, but from the side, from the other two raptors you didn’t even know were there.

The real, true, threat to this genre, it seems to me, comes from AI. And that was laid bare at Wildscreen on Wednesday afternoon.

Eline van der Velden

Former YouTuber Eline Van der Velden, founder and CEO of UK-based Particle6, and Christopher Paetkau, senior MD and Canada’s Build Films, felt initially like they’d been sent as deliberate provocateurs to tell the crowd all their jobs were about to become obsolete and, as Paetkau put it, “that’s a good thing”. Tactless, but then he did say he’d also got AI to write his wife’s anniversary card, so…

“Pre-production, ideas, budgets, scripting, it can do everything for you,” said Van der Velden. “Then cameras, you don’t need operators anymore because it will do it all for you.” *crowd gasps* “You may laugh, but I’m telling you. Everything is done for you. You wouldn’t send a camera in a helicopter anymore would you? You’d use a drone. This is the same.”

You can imagine how well that went down.

But then Paetkau played his clip of a polar bear he’d filmed in an Arctic Bay while out on a shoot. It was in sequence, it was immaculately edited, it was beautiful to look at, the voiceover was believable and earnest, the plot line was the bear’s struggles to adapt to a warming climate and melting ice destroying its food source. It looked, felt and sounded like anything else you’ve seen on Discovery, Nat Geo, Sky Nature, Love Nature or, yes, even BBC One at 21.00 on a Sunday night. The sort of thing that takes years out in the field.

“That took about two days,” he said. Two days.

“We spent under 24 hours there filming this and got footage that we wanted to put into a sequence,” he explained. “We went to the BBC’s Planet Earth, we took a script from ‘lion hunt’, copy and pasted into Chat GPT and altered it to the behaviour we described. Then we got ElevenLabs to produce a voiceover. From the day of filming to putting that together was two days.

“If you miss shots for the sequence, you can’t go back and get them. I can foresee a situation quite soon where the broadcaster will allot, say, 10% of the broadcast hour to AI generated content in service of the story. If I miss something, want to enhance that story, do it for conservation, or have some goal that I want to work towards then AI just becomes a tool to help you get there. I don’t see natural history as being some protected area, some last bastion holding onto nature.

“As AI grows, the audience is going to be totally comfortable, even in blue-chip, with something like that where you have a gap in the story, you can’t send somebody out, and so you use SORA.”

Rob Hifle, creative director at VFX firm Lux Aeterna, told the same panel this will need to be regulated, and said audiences would still value authenticity above all else. Mikael Osterby at Sweden’s SVT said it was the duty of public broadcasters to follow his channel’s lead in pushing back against this in the era of misinformation.

I’ve been attending television conferences for more than a decade. I’ve seen threats come and go. I remember in natural history some very esteemed producers were all in on 3D, and then VR. I’ve seen Netflix grow out of a DVDs in the post business. This felt big. In this environment, in this ‘new creative economy’, why is any broadcaster or streaming service, old or new, traditional or otherwise, going to pay millions of pounds for you to sit in South Africa for four years waiting for a giraffe to do something when you can film that giraffe for a day and there’s now a computer that can take the footage and turn it into whatever you want. It can make the thing turn a bloody summersault if you want it to.

Perhaps the audience will be like me and want to know it is an authentic shot. “There’s a reason the ‘making of’ bit at the end of Planet Earth is everybody’s favourite bit of the episode,” said one freelancer to me off stage. Personally, I really hope so. It would restore some faith in humanity. But over all these years I have never sat in a room of TV execs and seen a reaction of delegates like this one on Wednesday. It was audible, all around the room. When the floor was opened up to questions, in a room of 500+ people, it was quicker to count the hands that were down. Real genuine fear, from people whose job it is to get as close to lions as possible without getting eaten. And it was that clip that did it.

We’re out of a job.

Don’t you mean extinct?