The future of Bosnia-Herzegovinian public broadcaster BHRT is under serious threat due to lack of action by the authorities to tackle its financial and functional problems, warns Lejla Babovic, its deputy director general of development and international affairs.

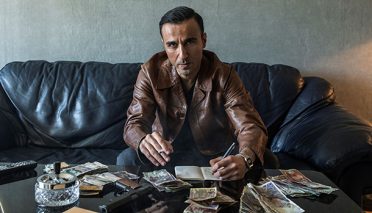

Lejla Babovic

To say that the structure of the TV industry in Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH) is highly complex is probably something of an understatement. In the case of public broadcasting, it is underpinned by the Law on Public Broadcasting System in BiH, which came into effect 10 years after the signing of the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement ending hostilities in the country.

At the heart of public broadcasting is an organisation known as Radiotelevizja Bosne & Herzegovine (BHRT), which its deputy director general of development and international affairs, Lejla Babovic, says is not, like many assume, an “umbrella” for all public services in the country.

Under the 2005 legislation, she adds, the public broadcasting system should consist of three broadcasters, namely BHRT, serving the entire country; RTVFBiH, aimed at the Bosnian Muslim-Croat population; and RTRS, based in the Bosnian Serb entity Republika Srpska.

There should also be a fourth legal entity, a “so-called” corporation, she says. But without implementation of amendments to the law to establish this corporation, BHRT has been playing that role since 2005. “Because of that, our position is very hard as we have 500 employees who should have been in the corporation but are still with us,” explains Babovic.

“The whole production and technical facilities are the responsibility of BHRT, and nobody cares if we have money or not,” she says.

The latter is a key point, as according to the law, receiver licence fees should be collected throughout the country by RTVFBiH and RTRS and then paid into a bank account administered by BHRT. BHRT can then retain 50% of the funds, with the remainder distributed equally between the two broadcasters.

This, says Babovic, worked well until 2017, after which RTRS decided to stop paying collected receiver licence fee money into the account. “That was when the main problem for BHRT began and now RTRS owes more than €45m [US$48.3m] to BHRT,” according to Babovic.

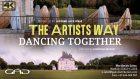

Long-running talk and music show Finally Friday

She stresses that BHRT, which operates a single TV channel and radio station, has more responsibilities than RTVFBiH and RTRS. It is, for instance, required to have technical centres and correspondents in all parts of the country. Furthermore, it must acquire the rights to major events, “and you know how much money that costs. The other two do not have these obligations.”

“To be precise, we are receiving 50% of the collected fee from 25% of the territory. We were supposed to receive 50% from 100% of the territory,” she explains.

Understandably, this has had a huge impact on BHRT, meaning “it’s really a problem to survive, to maintain the business,” Babovic says.

BHRT, nevertheless, continues to produce programmes, including news on a daily basis, current affairs, children’s, documentaries, entertainment and sport – in the latter case offering more than any other broadcaster in the country, according to Babovic.

Despite this, the financial constraints are limiting BHRT’s ambitions. “We do not have any money to produce any feature programmes, which we would like to do. Also, we are not able to be part of coproductions because of lack of money,” she says, but adds that by offering its equipment and services, it has helped in the production of several films.

While “grand shows on a Saturday evening” are out of the question, BHRT boasts one light talk and music show called Finally Friday, which has been running for 17 years. It also acquires some music concerts, says Babovic. “We are always doing our best to acquire sports rights, even when we are without salaries for a certain period.”

Sweet Revenge (Tatli Intikam)

Sport, in fact, plays a key role in BHRT’s output and she says viewers are quick to point out when some events are missing from its schedule, especially as they feel €3.50 a month is a lot to pay for a receiver licence fee. However, Babovic points out, few people complain about a packet of cigarettes costing €3.

Looking more generally at viewers’ tastes, Turkish soaps are the main product on the market. They are very well watched and have been shown for 15 years. Recent titles on BHRT include Sweet Revenge (Tatli Intikam), Joy of My Life (Hayatimin Nesesi) and My Lovely Family (Benim Guzel Ailem). All types of sports, especially football, basketball, handball and skiing, also achieve high ratings.

One area where BHRT cannot compete with commercial stations is popular entertainment shows, such as the singing competition It’s Never Too Late, which is shown on Nova TV. The channel is owned by United Media and is one of numerous stations operating in the country. They include N1, also owned by United Media; OBN, which is based in Sarajevo but under foreign ownership; Serbia’s TV Pink; and Al-Jazeera Balkans. Both public and commercial TV stations from neighbouring countries such as Serbia, Croatia and Montenegro are also widely watched.

There is also a production sector in BiH, but according to Babovic it only makes feature films.

Babovic points out that while cable penetration is at almost 100% in the country, allowing for the reception of more than 200 TV channels, the terrestrial network is not yet digitised. “We only have three [digital] ‘islands,’ in Sarajevo, Banja Luka and Mostar, otherwise it’s still analogue. The second phase will bring digitisation to the whole country,” she says.

Although BHRT streams its programming on a daily basis on its website and sometimes geo-blocks sports and movies, Babovic concedes that when it comes to using social media there still remains much to be done. She also believes it targets a mostly older (40-plus) audience and is “aware that youngsters need to have programmes on their mobiles, otherwise they will not watch them.”

Joy of My Life (Hayatimin Nesesi)

On a more positive note, she points out that BHRT has given permission to cable operators to offer its programming on a catch-up basis. Not every broadcaster does this and, in her view, it is “one of the good decisions of our management.”

Yet the situation for BHRT remains precarious.

In March last year, the European Broadcasting Union, of which it is a member, alongside the European Federation of Journalists and the South East Europe Media Organisation, called on authorities in BiH “to tackle the financial and functional problems” of BHRT in order to safeguard media freedom.

Indeed, Babovic believes BHRT’s parlous financial situation and the fact it is in “survival mode,” makes it hard to talk about its future plans. She is also pessimistic about the government and believes there is unlikely to be any change in BiH whilst the political structure in Republika Srpska is under Russian influence. Furthermore, she points out that recently a broadcaster in Republika Srpska, Una TV, came close to being taken over by Russia Today.

Babovic concludes that, according to many NGOs, BHRT is the most objective broadcaster in the country. “I think our main problem is we are not supported by any party. In Republika Srpska, [the broadcaster is] under the full control of the government and in the federation, under the ‘light control’ of the political parties.”

In this situation, BHRT finds itself alone, while the other broadcasters “have money and someone [to watch] their back.”