Grace period

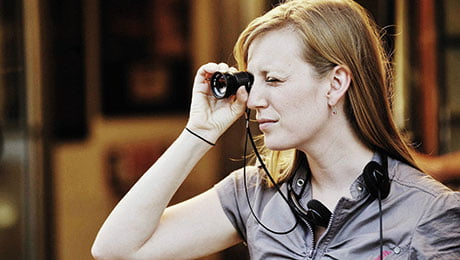

Sarah Gadon plays convicted murderer Grace Marks in Alias Grace

Netflix and CBC have thrown their support behind an all-star team of female creatives for six-part limited series Alias Grace, the second major Margaret Atwood adaptation to hit screens this year. Adam Benzine reports.

For all the talk of increasing diversity and gender parity in the television industry, the statistics remain dispiriting.

According to the US Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film’s report Boxed In 2016-17, women represented just 28% of the key creative positions (directors, writers, producers, exec producers, editors and so on) on broadcast network, cable and streaming shows in the US during the past 12 months. “The employment of women working in key behind-the-scenes positions on broadcast network programmes has stalled, with no meaningful progress over the last decade,” the report notes.

As such, while the all-female team assembled for the CBC and Netflix’s six-part period drama Alias Grace shouldn’t, in and of itself, be remarkable, the fact is they remain outliers in a still heavily male-dominated industry.

The 1840s-set miniseries, based on Margaret Atwood’s 1996 novel of the same name, has been adapted for the screen by Oscar-nominated writer-producer Sarah Polley (Away From Her, Stories We Tell). The show was produced by Noreen Halpern of Toronto- and LA-based Halfire Entertainment and all six episodes were directed by Mary Harron (American Psycho), with actor Sarah Gadon (11.22.63, Happy Town) playing the lead role of convicted murderer Grace Marks.

For showrunner Polley, who first began chasing the rights to the project at the age of 17, the show is the result of a nearly 20-year attempt to bring the novel to the screen.

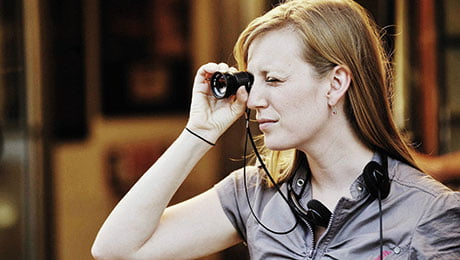

Sarah Polley spent almost two decades trying to get the novel to the screen

“It went through a long process where the rights bounced around between various companies,” she recalls. “At one point, Working Title had it and asked me if I would consider writing and directing it, but the contract just never came through. After seven or eight months, it became clear it was never going to happen.”

When the rights eventually lapsed, Polley swooped in to acquire them. But even then it would take several more years for writing to commence, as other projects and two young children took precedence. Though she originally envisaged Alias Grace being a movie, “it became really clear to me that in order to fit this into a two-hour film, I would have had to erase a lot of the things I loved about the novel,” Polley says.

“I always thought it could make a great feature – I still think it could – but it would necessitate paring it down so that the context, the political history and the world they live in would have had to shrink considerably. And what’s the point in doing it if you have to shrink the things you love?”

Polley attributes the fact the show was greenlit by two female commissioners – Sally Catto, CBC Television’s general manager for programming, and Elizabeth Bradley, Netflix’s VP of content – as the biggest reason it could hire a powerhouse of female creatives to bring her passion project to life.

“The difference here is the gatekeepers were women, and I do think that makes a huge difference in terms of getting women financed,” she says. “I wish that weren’t the truth, but I think it is.

“The ease with which this got financed was so remarkable to me, and it’s the first time I’ve been sitting across the table from just women, so there’s something in that that’s really hopeful. The more women we have in those kinds of positions, the more female filmmakers and producers we’re going to see.”

Director Harron agrees. “The one thing we can do now is get more women on the crew,” she says. “There’s a below-the-line liberation movement that needs to happen. If we’re truly changing the industry, you need to work on every level.”

Having worked on predominantly male-controlled sets in the past, both noted certain differences on the Ontario shoot for Alias Grace. Polley reflects that “when you’re working with women, you don’t have to compartmentalise or segregate your life in the same way.

Atwood adaptation The Handmaid’s Tale was an multiple Emmy winner for Hulu

“Conversations about children, childcare and life are sort of intertwined with conversations about work and there’s a seamless moving between those things, which I’ve found less often with men,” she explains, “partly because, I think, it’s less socially acceptable for men to talk about those things. It’s actually one thing women have a lot more freedom in than men, to talk about their children and wanting to make time for that.”

As such, “there’s a big shift women can make in this industry that will be easier for women to make than for men to make,” she continues, “which is to break down the barriers not just of more women making things, but also the structure of how we make films.

“At the moment, it’s impossible to work on film sets and be an involved parent or caregiver for an elderly person. And I hope that’s one of the things women do as they move into these positions.”

While Polley outlines clear differences in her on-set experiences, for many of the creatives C21 spoke to for this feature, addressing the fact that the show is helmed by a predominately female ensemble proved thorny.

“I struggle with the idea of what made it different, because all directors are different,” says lead actor Gadon. “To reduce them to just the question of what made them different by their gender is tough, because part of the struggle with women in the film industry is that we’re trying to break out of these kinds of binary definitions of who we are and what our roles are.

“So when you then answer questions in a very binary way, it seems a bit reductive. That being said, the women who came together to make this project were all really intelligent and really creative, and at a level worthy of Margaret Atwood to make this work.

“The book deals with female subjectivity and female identity, and who better to tackle that subject than really talented women who have a history in working with very psychological and violent work?” she adds. “On a very simple level, it was really the material that demanded the people who came together to make it.”

Halpern, who is founder and president of Halfire, notes: “While it’s a gross generalisation, with women there is somewhat more of a sense of, ‘Let’s sit down, let’s talk about it, let’s work it out.’ No one worked any less hard; if anything, people worked harder and were more committed because they felt there was such a sense of collaboration and inclusion.”

“And of being listened to,” Harron adds.

Beyond the make-up of its creative team, Alias Grace is notable for being the first major period drama coproduction between Canadian pubcaster the CBC and international SVoD service Netflix. The series premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September before launching on the CBC later that month. It then debuted in the US and all other Netflix territories on November 3.

Halpern expects to see more such copros in future as Canadian nets increasingly cut costs by partnering with global streamers. “There was also a show that sold after ours but aired before ours, Anne with an E, which has been a very successful partnership between the two of them,” she notes. “There are amazing stories to be told in Canada, there are amazing creators and filmmakers, and one of the ways we’re going to need to tell these big stories is to find partners.”

Alias Grace hit TV screens hot on the heels of another Atwood adaptation, Hulu drama The Handmaid’s Tale, which swept September’s Primetime Emmys with eight wins. The success of that series raises expectations for Polley’s adaptation, although she sees that as a clear positive.

“It helps a lot,” she says. “It made some people on our team nervous. But to have people already interested in Margaret Atwood… suddenly she’s the biggest name in television.

“I think it will make it a lot easier for us finding an audience than it would have before The Handmaid’s Tale. It’s amazing to look back and to look forward through her lens. She’s looking back at where we came from, what women’s history is, what the history of immigration is and what kind of society we came from [in Alias Grace], and she’s looking forward to what kind of society we might end up being [in The Handmaid’s Tale].

“That’s a really interesting conversation to be having,” Polley adds. “It’s useful now, politically, to be looking forward and backward at the same time. I see it only as a positive.”

.jpg)