Baring FAANGs

As Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google step up their efforts to reach children, should the industry be welcoming, wary or worried? Nico Franks reports.

The acronym FAANG may be a catchy way to label the five tech giants that are having an increasingly strong influence over our daily lives, but it also risks amalgamating them into one big digital bogeyman.

The reality is that those five are striving for dominance in their own fields in different ways, guided by moral compasses of varying strengths. Some of the biggest are now stepping up their offerings for young audiences, which isn’t necessarily a cause for concern, and in many instances should be welcomed.

Greg Childs

Take Netflix, which has pumped millions of dollars into the business in pursuit of high-quality, original programming, while Amazon has shown a similarly strong commitment to quality children’s programming since beginning its original content push in 2012.

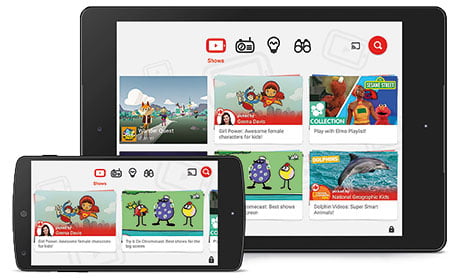

Google has a far more checkered past and present when it comes to children’s content on its video-sharing behemoth YouTube and offshoot YouTube Kids. PR fail has followed PR fail in recent months at Alphabet, the parent company of Google, as it has allowed low-quality, even potentially harmful, content masquerading as family-friendly fare to appear on YouTube Kids.

Apple, aside from its influence in the children’s app market via the App Store, remains a relative unknown in the children’s content space. However, its appointment of Tara Sorensen at its content arm suggests it is pursuing a strategy similar to those of Netflix and Amazon, where Sorensen was most recently head of children’s programming.

Then there’s Facebook, which is arguably the least popular company of the five among children, given their parents’ preference for posting pictures of them on the platform. Nevertheless, the social media giant has revealed in the past six months a number of initiatives that suggest it is workingto bring the age of its average user down a decade or two.

Messenger Kids, a version of its messaging service for under-13s, launched in the US last year. Meanwhile, its video platform, Facebook Watch, is working on an English-language version of Norwegian teen drama Skam (Shame), produced by Simon Fuller’s XIX Entertainment.

Facebook Watch is adapting Norwegian teen drama Skam

The show, which explores subjects such as eating disorders and sexual identity among a group of teenagers, involves the audience via social media platforms such as Instagram, which Facebook owns, in addition to weekly episodes broadcast live online.

For many, these developments at Apple and Facebook are an inevitable part of the evolution of the entertainment industry, as new entrants plant their flags in the sand and established players are forced to adapt to the new order.

In the view of UK media regulator Ofcom, this is creating a “rush to scale,” principally through mergers and acquisitions. Take Disney swooping on various 21st Century Fox assets and Comcast’s counter-offer for Sky, or AT&T’s attempted purchase of Time Warner. Ofcom points out that, if approved, the market capitalisation of each of Disney-Fox, Comcast-Sky and AT&T-Time Warner would be less than half of the market capitalisation of Facebook (US$532bn), Amazon (US$735bn), Alphabet (US$790bn) or Apple (US$911bn).

“Just as traditional broadcasters faced the challenge of digital pay TV platforms two decades ago, they are now seeking greater global scale to compete with the digital giants,” said Ofcom in a recent report on public service broadcasting in the digital age.

Greg Childs, director of UK kids’ media lobbying group the Children’s Media Foundation (CMF), says that the FAANG companies’ activities are “interesting and potentially all for the good” of the industry. “There’s a lot more money sloshing around in the kids’ market. Far be it from me to turn away people who might want to put money into UK production,” says Childs.

Adam Minns

However, the former head of digital at BBC Children’s also emphasises that many of the companies really have to “get their act together” when it comes to ensuring their platforms are safe places for children to watch content, especially given the years of warnings some of them have received.

“This is not just for the sake of the audience, which is our primary concern at the CMF, but for the health of the industry,” says Childs. Taking Facebook as an example, Childs says he would not be against the company making programming in the UK aimed at teenagers, and nor is he necessarily against Messenger Kids – as long as it is a genuinely safe platform.

“If Messenger Kids can be made to work as a safe alternative and they can attract an audience to it that is under the age of 13 without capturing data that puts them the wrong side of the COPPA [Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act] regulations, then good luck. In the same way, we’ve said to YouTube, ‘Good luck with YouTube Kids.’ That’s the direction we hoped they would have travelled in, but they’ve only taken a few steps down what is a very long road,” says Childs.

Operating outside the traditional broadcasting system has meant that, so far, the FAANG companies have been expected to self-regulate – with varying degrees of success. Netflix hit a bump when its young adult drama 13 Reasons Why faced criticism for its depiction of teen suicide, which, ordinarily, would have been subject to strict guidelines in countries such as the UK to prevent copycat actions among young viewers.

Netflix’s controversial young-adult drama 13 Reasons Why

The SVoD giant, which also received praise for its series drawing attention to the problems teenagers can face, later added a warning at the start of the show in addition to those before graphic scenes following outcry from mental health charities.

Google, meanwhile, has pledged to step up its efforts to self-regulate following the well-known controversies surrounding inappropriate content on YouTube and YouTube Kids.

However, at the height of the storm around the platform towards the end of last year, Matt Brittin, president of EMEA business and operations at Google, rejected the idea that YouTube – which reaches more than 40 million people per month in the UK, according to data cited by Ofcom – should be regulated like a broadcaster.

“I don’t think any businessperson is going to put their hand up and say, ‘We need more regulation.’ But we are regulated. We don’t have the same set of rules as a newspaper or television station and I think that’s appropriate,” said Brittin. “We want to make sure that no video that shouldn’t be on the platform is on the platform. But 480 hours is uploaded every minute and it’s an open platform. And you don’t want to lose the benefits of that.”

BBC director general Tony Hall

For all the negative PR surrounding YouTube, the platform remains a key part of most children’s broadcasters and producers’ distribution strategies. Similarly, Netflix and Amazon are now some of the first doors producers knock on when attempting to get new shows off the ground. But broadcasters’ voices are rising when it comes to arguing for more of a level playing field regarding regulation.

Jonathan Thompson, CEO of Digital UK, which supports UK terrestrial broadcasters, says there’s an “imbalance” between the requirements on broadcasters and major international SVoD operators.

These views reflect those of BBC director general Tony Hall, who recently called for reform to be “sped up to keep pace with the current challenges,” as “the global media landscape is soon likely to be dominated by four, perhaps five, businesses on the west coast of America.”

And while their business may be welcomed by some, it’s clear many feel the health of the broadcast sector could be undermined if the FAANG companies are not more strictly regulated soon.

Adam Minns, executive director of the Commercial Broadcasters Association (COBA) in the UK, the industry association for cable, satellite and digital broadcasters and their on-demand services, believes the playing field isn’t level and gives the new entrants an unfair advantage in the fight for viewers’ eyeballs.

“We feel much closer to public service broadcasters than we do to social media services. Increasingly, that huge disparity in levels of regulation is becoming a problem,” he says.

Google came under fire over YouTube Kids

“We believe in competition. The problem is it has got to be fair. When you’re competing with one hand tied behind your back because the company that is increasingly your competitor is not subject to the same rules as you then that becomes a policy problem,” adds Minns, who fights the corner for firms like Turner and The Walt Disney Company.

Minns admits it is a very tricky problem to solve but suggests that one sure way of avoiding a worse situation is to ensure traditional broadcasters don’t come in for even greater regulation in the future.

While the European Commission (EC) is reportedly preparing to hit Google, Facebook and Apple with a ‘digital tax’ on European Union (EU) turnover – estimated to raise about €5bn (US$6.2bn) a year – changes are afoot regarding how the companies are regulated in Europe.

The EU is currently deciding how to update the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) in recognition that TV broadcasting, VoD and user-generated content are currently subject to different rules and varying levels of consumer protection.

“The scope of the AVMSD is to be amended so that certain provisions also apply to video-sharing platforms. The aim is to harmonise the regulation of broadcast services and video-sharing platforms in certain areas. However, there are differences in the ways that the two types of services are operated and managed in practice,” says Emily MacKintosh, director, IP, transactions and commercialisation at European law firm Fieldfisher.

The revised AVMSD directive includes measures to force VoD providers to respect quota requirements for works of European origin and to make a financial contribution to the production of European works. But Minns is aghast that the debate has been widened to include a potential levy on linear channels, something he describes as “out of step with reality.”

Imposing a levy of an unspecified amount on a channel in every EU country where it is available “seems ridiculous” at a time when broadcasters are facing increased competition, says Minns.

“VoD services are likely to be subject to the levy, but they argue, ‘If you’re doing it to us, you should be doing it to linear channels as well.’ We say once you start investing billions and billions of pounds into European content and are subject to all of the different advertising and editorial restrictions that we are, then maybe you have a point. But until that point, you don’t,” he adds.

The process of bringing the new and old worlds of broadcasting more in line with one another on a regulatory level is clearly convoluted, overdue and essential for the protection of children and the long-term health of the industry.

Crucially, embracing the FAANG companies’ efforts to supply content for children should not come at the expense of the vital contributions of traditional broadcasters.

.jpg)